|

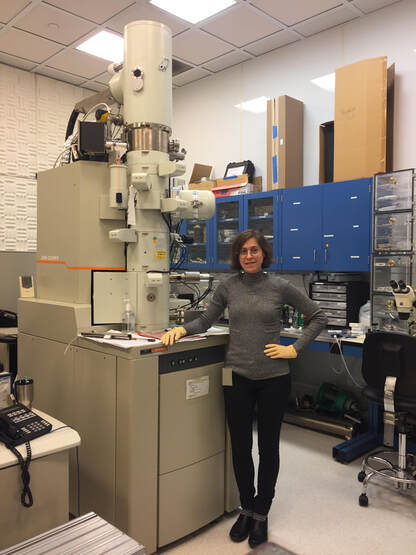

Today's guest studies some of the largest objects in the solar system by examining some of its smallest objects. Dr. Sheri Singerling is a cosmochemist and author. She works as an instrument specialist for NanoEarth at Virginia Tech, where she uses scanning electron microscopy (SEM), focused ion beam (FIB), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to unravel mysteries about our early solar system. Sheri, you’ve worked at a variety of interesting places including the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, US Geological Survey, and Natural Museum of Natural History. Tell us a bit about yourself and your career. What are you passionate about? My background is in geology, but I’m a bit unusual because I study rocks (and dust) from space. I’ve always been fascinated by astronomy, but I didn’t really think to go into physics until I was already well into my geology degree during college. I figured out that I could combine my interest in rocks and minerals with my love of space by studying meteorites. So that’s what I did and am still doing! For my graduate degrees, I looked at meteorites from different types of asteroids, and then after I finished my doctorate, I had an excellent opportunity to study stardust (yes, actual dust from stars) for a couple of years. I investigate meteorites and stardust using really powerful microscopes called electron microscopes. These use a beam of electrons instead of light to image samples, and this lets us see to very high magnification (over 1 million times) and down to very small scales (the nanoscale). I’m obviously very passionate about studying these kinds of samples and learning about the Solar System in its earliest stages. It’s so fascinating to me that just by looking at these pieces of rock, we can learn about all the complex and strange things that were happening billions of years in the past. Dr. Singerling standing next to a microscope (TEM) that she uses in her stardust research. How did you first get interested in science and nanotechnologies? I’ve always gravitated towards the sciences. It was always my favorite subject in school, but for some reason, I was under the impression for the longest time that only “geniuses” could become scientists. I had really good grades, but I definitely did not feel like I was “smart” enough to be a scientist. Looking back, it seems strange that I thought that way, but part of the problem is that, as kids, we don’t see how science really works. So much of science is making mistakes and learning from them, not being “smart”. In any case, once I was in college, I took an introductory geology course as my science credit and, from that, realized that I could be a scientist. I will say that the nanoscience part of my expertise is much more recent. It was only when I started my doctorate that I started using a type of really powerful electron microscope that images down to the nanoscale. Because of that, I had to start thinking like a nanoscientist. Your Twitter bio lists you as a “cosmochemist”. For those who don’t know, what does a cosmochemist do? A cosmochemist studies cosmochemistry. Nothing like defining a word by using another word! Cosmochemistry is just a fancy term for the study of elements, their abundances, and where we find them (which minerals) in meteorites. It can give us clues about the processes happening in the early Solar System. For me, it’s not the kind of chemistry most people usually imagine, where you’re in a lab with a lot of chemicals and wearing a lab coat, safety glasses, and gloves all day. It’s more the periodic table kind of chemistry. I think a lot of elements and how they behave with one another. When people think of nanotechnology, they often think of new materials and medical technologies made out of tiny particles. You study the early solar system. What can tiny things teach us about something as large as the solar system? That’s an excellent point and one I also ran into when I first started thinking about myself as a nanoscientist. Anyone who either makes or looks at things on the nanoscale can call themselves a nanoscientist because we are all having to view our work through the lens of the very small. Materials behave very differently on the nanoscale. This is true of materials that we make and also those that are naturally occurring, like what I study. The reason I look at tiny things to learn more about the Solar System is because that’s where a lot of the secrets about how it formed are hiding. Most of the information about the Solar System’s beginnings has been obscured by more recent processes, especially on the Earth where we have things like plate tectonics and weathering changing the surface. Small bodies, like the asteroids, have been much less affected and still have lots of information about their past. That being said, we usually can’t just look at images of an asteroid to know what’s really going on with it. Ideally, we want information on the minerals that are there, which requires us to look on smaller scales. Something as simple as observing clay minerals in a meteorite can tell us that the asteroid the meteorite came from had water on it at one point. We now think that most of the water on Earth, including in all of us, was delivered by asteroids. Your current job is at Virginia Tech’s NanoEarth. Tell us about the interesting work being done there. NanoEarth exists to bring the nanosciences to the geosciences. Historically, the earth and environmental sciences have been relatively slower at incorporating nanoscience into research. Other fields like physics, chemistry, biology, and engineering have really embraced using nanoscience tools, but the geosciences have lagged behind. This is unfortunate, because, as I mentioned, there is so much we can learn about larger-scale processes from nanoscale investigations. At NanoEarth, we work with researchers interested in using nanoscience techniques and help them develop their projects, collect the data, and interpret the results. Anyone is welcome to participate, and we’re always looking for work to collaborate on. Our website has more information on how to apply. One of the things I love about conversing with scientists is that they often have fascinating interests and hobbies even outside of their research. You self-published a novel, The Neohumanoids, in 2014. What’s it about and what led you into creative writing? Creative writing is definitely a passion-project for me, and like science, it’s always been something that I’ve loved doing. I actually wrote Neohumanoids way back in 2006 and only got around to self-publishing it when I realized that was an option. It’s a science fiction novella (a short novel) about a scientist in the early 1900s who figures out how to stop aging using genetics. Like most of my creative writing, it’s hard science fiction, which is a subgenre of science fiction that presents the science very realistically and with a lot of detail. I find creative writing to be a nice outlet for my more artistic side. That’s not to say that you can’t be artistic in science, but scientific writing is very constraining. In science papers, you are trying to present your findings in a very clear, concise way. It’s nice to get to break the rules and really do whatever you want in creative writing. I’m actually just wrapping up edits to a new novel I’ve been working on the past couple of years, but I’ll be trying the traditional publishing route this time around. Wish me luck! What advice would you give a 12-year-old who isn’t sure if she’d rather be a scientist or an author? I would say, you can be both! There are plenty of examples—Issac Asimov, Arthur Clarke, and Carl Sagan to name a few. What really matters is doing what you love. There is always time to figure things out, and when you are still a student, you should use the opportunity to try out as many different subjects as you can. Being well-rounded is useful to both scientists and writers. Explore! You describe yourself as a passionate environmentalist. If you had to recommend one habit our readers could adopt to be more environmentally friendly, what would it be? There are so many choose from, but if it had to be down to one, I would say that composting is an easy habit to pick up that makes a huge difference. Composting is just recycling your food scraps into fertilizer rather than throwing them in the trash. If you have your own yard, you can do backyard composting, but if you’re in an apartment, you can try worm composting. If you’re lucky enough to live somewhere that offers it, there are also composting collection/drop-off programs all over. These have the added bonus of usually also accepting meat and cheese scraps, which you can’t compost if doing it on our own. You could also push your local officials to implement such a program if you don’t already have one. Composting is an amazing science project of its own, and it does wonders for cutting back on greenhouse gas emissions. Did you know that everything you send to the landfill doesn’t actually break down? Landfills are designed this way. Why send food scraps to landfills if we can break them down ourselves? Last Question: If you had to hire a nanobot to do a job for you, what job would you hire it to do? Could I hire a swarm of them to do my dishes? I really spend so much time on dishes somehow. No but seriously, I would say I’d hire a nanobot to do a final pass on the samples that I make so that they were as nice and thin as possible. In my research, I use a technique called the focused-ion beam (FIB) to cut a thin slice of my meteorite or stardust samples. I look at these on the transmission electron microscope (TEM), which requires very thin (~100 nanometers) samples so that the electron beam can go through the sample. One of the most time-consuming parts of my research is just preparing these thin slices with the FIB. I’d be thrilled to have a nanobot do all the stressful final touches on my samples. That might cut back on some of my gray hairs. Sheri, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us today! We'll get to work on the dish washing nanobots. If you'd like to learn more about the Sheri, you can find her on Twitter or check out her novella The Neohumanoids. To learn more about NanoEarth, visit their website. Want to keep up to date on the latest happenings at DNP123? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed